Caricature of George Orwell by illustrator Ralph Steadman

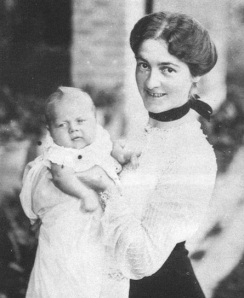

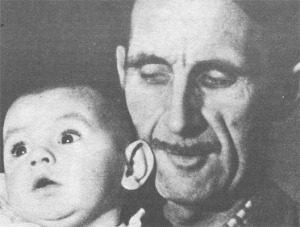

Eric Blair, with his mother Ida, in the autumn of 1903

1. His Name is Eric, He Was Born in India and His Dad Was In the Opium Biz

His father, Richard W. Blair, was a civil servant employed by the Opium Department of the British Indian government in Motihari, India. His job was to oversee the growing of opium by the Indian farmers. His mother was Ida Blair (nee Limouzin) and he had an older sister by five years named Marjorie (also born in India). By the time Eric was a year old, Ida had moved her and the children to England. Eric never returned to Motihari. When Eric was five, his sister Avril was born; conceived during one of the rare times Richard was able to get leave.

Avril Blair, circa 1913

2. His First Word Was “Beastly”

Because, as the future writer of Nineteen Eighty-Four, OF COURSE IT WAS!

Marjorie, Avril, and Eric Blair circa 1909

3. He Had a Few Boyhood Homes

First they moved to Henley-On-Thames, into a house Ida called “Ermadale” (Ida liked to tell others that it stood for ERic and MArjorie). Then they moved to Shiplake, into a house called “Rose Lawn”, where Eric spent most of his childhood. They would finally settle down in Southwold (at 36 High Street, also called “Montague House”) in the early 1920s to the late thirties. In Southwold Avril would become a successful entrepreneur after opening up her own teashop, called The Copper Kettle. The countrysides explained in Coming Up For Air and the Golden Country in Nineteen Eighty-Four were based on the countrysides around Shiplake.

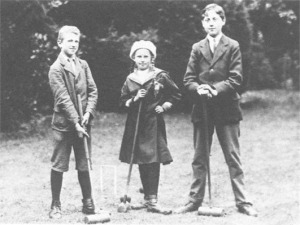

Prosper and Guinivere Buddicom, and Eric Blair

4. His Childhood Wasn’t THAT Bad. Well, Not ALL of It.

As a wee little lad Eric would hang out with the bigger boys of Henley, the leader being the older Humphrey Dakin. He was a good friend of Marjorie (so much so that they would end up marrying and have three children), so he was forced to tolerate little Eric. He thought of Eric as whiny and prone to tattling to the adults.

He attended boarding school at St. Cyprian’s, where he met fellow future author Cyril Connolly. His memories of the school would be written in the 1946 essay Such, Such Were the Joys, and were presented as a Nineteen Eighty-Four lite. Was it as bad as he wrote? It was probably in the middle—Orwell liked to exaggerate for literary reasons. Later alumni’s would talk about hating their time and others enjoyed theirs. Connolly wrote a scathing account of his days there, but about ten or so years later would re-examine his views.

However, a friend from Shiplake, Jacintha Buddicom, said that she and her family always saw Eric as a happy child (of course he was—he was out of school; he was probably on some wonderful high). She and her siblings met Eric when they saw him standing on his head in his backyard. “You are noticed more if you are standing on your head than you are right way up,” was his explanation. It worked! After the early 1920s, Orwell would lose contact with Jacintha (his first crush) until the late 1940s when she realized that the author of Animal Farm was her childhood friend–Eric the FAMOUS AUTHOR.

Eric, Ida, Avril and Richard Blair circa 1914

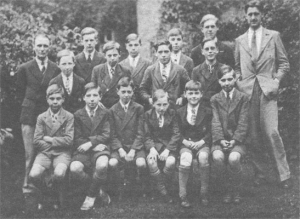

5. He Attended Eton, From 1917 to 1921

Eric did so well at St. Cyprian’s that he was able to get a King’s Scholarship for Eton, the school of princes and non-princes alike. As soon as he started Eton he quit trying, telling others he needed a break from all the schoolwork from his childhood. Eton was a lot more free, so it was easy to slack off. He did participate in Eton’s Wall Games, though, and earned his colors of which he was quite proud. Orwell tried to play as if Eton wasn’t that big of a deal, but throughout his life he would be proud of the place and others would note his “Eton accent” that he would try to shed. Coincidently, author Aldous Huxley (who would write Brave New World, another milestone in dystopian fiction) was Blair’s French teacher for a semester. Huxley had an extremely bad eyesight, to the point of almost being legally blind, and the other boys would make fun of him something terrible. To his credit, Blair never made fun of Huxley and would try to get the other boys to stop. Later on, Huxley would write Orwell a letter after Orwell sent him a copy of Nineteen Eighty-Four. In it, he compared the two worlds and ultimately decided that his was the correct prediction. As of this writing, I am not sure if Huxley knew Orwell was a former student:

Wrightwood. Cal.

21 October, 1949

Dear Mr. Orwell,

It was very kind of you to tell your publishers to send me a copy of your book. It arrived as I was in the midst of a piece of work that required much reading and consulting of references; and since poor sight makes it necessary for me to ration my reading, I had to wait a long time before being able to embark on Nineteen Eighty-Four.

Agreeing with all that the critics have written of it, I need not tell you, yet once more, how fine and how profoundly important the book is. May I speak instead of the thing with which the book deals — the ultimate revolution? The first hints of a philosophy of the ultimate revolution — the revolution which lies beyond politics and economics, and which aims at total subversion of the individual’s psychology and physiology — are to be found in the Marquis de Sade, who regarded himself as the continuator, the consummator, of Robespierre and Babeuf. The philosophy of the ruling minority in Nineteen Eighty-Four is a sadism which has been carried to its logical conclusion by going beyond sex and denying it. Whether in actual fact the policy of the boot-on-the-face can go on indefinitely seems doubtful. My own belief is that the ruling oligarchy will find less arduous and wasteful ways of governing and of satisfying its lust for power, and these ways will resemble those which I described in Brave New World. I have had occasion recently to look into the history of animal magnetism and hypnotism, and have been greatly struck by the way in which, for a hundred and fifty years, the world has refused to take serious cognizance of the discoveries of Mesmer, Braid, Esdaile, and the rest.

Partly because of the prevailing materialism and partly because of prevailing respectability, nineteenth-century philosophers and men of science were not willing to investigate the odder facts of psychology for practical men, such as politicians, soldiers and policemen, to apply in the field of government. Thanks to the voluntary ignorance of our fathers, the advent of the ultimate revolution was delayed for five or six generations. Another lucky accident was Freud’s inability to hypnotize successfully and his consequent disparagement of hypnotism. This delayed the general application of hypnotism to psychiatry for at least forty years. But now psycho-analysis is being combined with hypnosis; and hypnosis has been made easy and indefinitely extensible through the use of barbiturates, which induce a hypnoid and suggestible state in even the most recalcitrant subjects.

Within the next generation I believe that the world’s rulers will discover that infant conditioning and narco-hypnosis are more efficient, as instruments of government, than clubs and prisons, and that the lust for power can be just as completely satisfied by suggesting people into loving their servitude as by flogging and kicking them into obedience. In other words, I feel that the nightmare of Nineteen Eighty-Four is destined to modulate into the nightmare of a world having more resemblance to that which I imagined in Brave New World. The change will be brought about as a result of a felt need for increased efficiency. Meanwhile, of course, there may be a large scale biological and atomic war — in which case we shall have nightmares of other and scarcely imaginable kinds.

Thank you once again for the book.

Yours sincerely,

Aldous Huxley

A small newsreel of the 1921 St. Andrew’s Day Wall Game at Eton exists. It can be found here. Blair is the fourth from the left, as the boys are walking towards the camera. It is the only film known to exist of George Orwell.

6. He Was a Policeman in Burma

Blair was not keen on even more schooling, so he gave up ideas for university and decided to head straight into some kind of work. Throughout his teenage years he would wax poetic about the East, as it was the place of his birth, and the place of Rudyard Kipling. He decided to do some sort of Imperial Civil Service, like his father, but decided to go to Burma instead of India. Blair still had quite a few members of his mother’s family in Burma, including his grandmother.

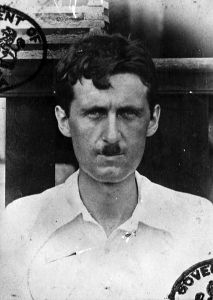

He would become a policeman and be put in charge of some 200,000 people. He spent his free time reading, writing a little, and having servants tend to his every need. He acquired some tattoos on his knuckles and grew his famous mustache.

But before too long, Blair became disillusioned with the realities of working for the British Empire. While his father had stuck with Imperial life for at least forty years, Eric decided to get out after five. After contacting dengue fever, he was allowed leave in 1927. He never re-applied. His memories of this time of his life can be found in the book Burmese Days and the essays Shooting An Elephant and A Hanging.

7. He Willingly Lived a Life of Poverty in Paris, and One of a Tramp in London—But Help Wasn’t Far Away

Out of Burma, he now concentrated on being a writer full time. He wanted to write about the lives of the underdogs, and decided that the only way to do that is to become one of them. In Paris he washed dishes, and in London he became a tramp–all the while talking to people in actual poverty. Because Orwell was never in danger of actually spending a huge amount of time in the gutter. In Paris he had his Aunt Nellie to help him with food when he was desperate. She also helped him find the room in rue Pot de Fer and would introduce him to Henri Barbusse, the man who published his first paid piece in 1929. In London he had friends, and he spent a lot of his hop-picking days while still living in Southwold. His family would demand him to go take a bath as soon as he got home.

8. George Orwell Is, Of Course, A Pen Name

He had several pen names thought up, but in the end chose “George Orwell” because, as he said, “It is a good round English name.” He was rather sketchy on where Orwell came from but it could have come from the Orwell River. Another interesting and possible explanation is “Orwell” was the name of a pre-race favorite horse in the 1932 Epsom Derby. George may have come from his own Uncle George Limouzin, the youngest brother of his mother Ida. But why did he come up with a pen name in the first place? For one, he’d always disliked “Eric Blair”. He was also afraid of shaming his family. Over the years George Orwell would have his own life, seperate from Eric Blair. Orwell had his own set of friends, and Blair HIS own. It was part of Orwell’s love of putting his life into compartments. Friends would talk about how Orwell would keep friends they had never met, as if Orwell made an effort to keep everybody from knowing everyone else. His first book was Down and Out In Paris and London.

Another clever reason for “Orwell” was because he wanted a name that started with a letter in the middle of the alphabet. Why? Because, as he stated in a letter to bookseller Louis Simmonds, it allowed for his books to be placed in the middle shelf in bookstores. Not too high, where customers can’t see and not too low where he would be near the customer’s feet.

9. He Was Superstitious

There is no debate: Orwell WAS an atheist. He identified as one. But he also still hung onto the traditions of the Church of England, and many of his morals were Christian-based. He was also quite superstitious. While in a Wallington church yard, he could have sworn he saw a ghost. He had the belief that people could do secret black magic on a person’s name—another reason he chose a pen name. In his early Eton days, he and a schoolmate created a voodoo doll out of soap of an older kid they felt bullied them. The kid would end up breaking his leg and, later, dying of cancer. Orwell felt guilty about this fact for the rest of his life. In Burma, he got small blue circles tattooed on his knuckles to ward off bad luck.

10. He Held Various Other Odd Jobs Before Becoming a Full Time Author

Lots of authors are teachers before making it big, and Orwell was no exception. He became a tutor to a disabled boy and then a teacher at the Hawthorns High School for boys for a few semesters. After that he became a teacher at Frays College in Uxbridge. Upon moving to London he worked part-time at Booklovers’ Corner at South Green in Hampstead. The property for the bookshop changed hands several times over the years, and is now a hamburger restaurant. A plaque indicating that Orwell once worked there is on the building, on Pond Street. Booklovers’ Corner would have some lasting affect, as he wrote about it in the essay Bookshop Memories and the book Keeps the Aspidistra Flying. He got his first major writing assignment checking out miners in the impoverished north of England and wrote The Road to Wigan Pier. He left odd jobs completely in the 1940s, when he began to write full-time doing correspondences, essays and reviews for various literary magazines and newspapers.

11. He Settled Into Domestic Bliss In A Typical English Cottage—For a Short Time, Anyway

At a party in Hampstead Heath he met Eileen O’Shaughnessy (1905-1945), a psychology student at Oxford who once had a class with JRR Tolkein, and told his friend, “That is the type of girl I would like to marry.” They married in June of 1936 at the church in Wallington, in Hertfordshire. They maintained a cottage called The Stores, where they sold this and that to the villagers. They made the most money off of the candy they sold to the village children. The cottage itself was terrible (it was poorly heated, it leaked, and had a tin roof that made a terrible noise when it rained), but they loved the adventure of it. They grew some vegetables and kept a few chickens, and goats. It was during his time at The Stores (after they had come back from Spain) that he thought up Animal Farm, and incorporated much of his life in Wallington into the book: his goat Muriel, for example, help from Eileen, and being able to view the large farm down the road from his spot upstairs—called Manor Farm. But you can’t make Orwell settle down for long—soon it was off to Spain and then Marrakech!

12. He Fought In the Spanish Civil War

During the 1930s, Fascism was alive and well throughout Europe. Hitler gained power in Germany. Mussolini in Italy. Stalin in Russia. And Francisco Franco was attempting to do the same in Spain. Orwell believed that one should talk the talk only if one walked the walk (well, not in those words of course) and he proved this by going to Spain to fight on the Republican side against the Communists. In 1937 he was shot by a sniper’s bullet in the throat. It missed his jugular by (in the words of Maxwell Smart) THAT MUCH. He hadn’t fought for that long, but his experiences would change his life. From that time forward he became an enemy of Communism, and favored Socialist causes (but wasn’t above pointing out the hypocrisies of his own team either). The story of a revolution gone sour and betrayed would be the theme of Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four. A more direct work dealing with Spain was Homage To Catalonia. Before leaving Spain, there was a raid on his and Eileen’s hotel room and several people whom Orwell thought were good friends turned out to be Communist spies. To this day a diary written by him is possibly still in the NKVD archives in Moscow. This paranoia over Communists would haunt him until the day he died.

After returning to Wallington for a short while, he and Eileen (with money donated secretly by a friend) went to Marrakech in hopes of the dry air helping with Orwell’s health. By this time Orwell had been officially diagnosed with Tuberculosis by his brother-in-law, Dr. Laurence O’Shaughnessy (whom would be killed in Dunkirk during World War II). While doing his usual farming of vegetables and keeping of at least one goat and chickens, Orwell wrote out most of Coming Up For Air. His father, Richard Blair, would die shortly after the publication. The last thing he heard before dying was of the review of Coming Up For Air, read to him by Marjorie. Orwell finally found approval from his father.

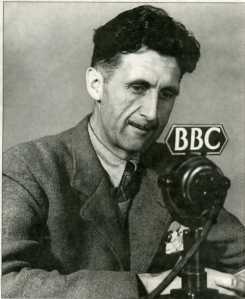

13. He Worked For the BBC

Orwell couldn’t find work in the military, due to his bad lungs, so he eventually found work at the BBC. He did broadcasts for the Eastern Services department. Later on Orwell considered his time at the BBC “two wasted years” but they were anything but. He developed short plays, educated lectures echoing Open University, collaborations with TS Eliot and Dylan Thomas (photo above shows Orwell leaning over TS Eliot), and news broadcasts. Much of the imagery of Winston Smith’s work life at the Ministry of Truth was taken from Orwell’s time at the BBC, from the canteen to the work station. The building where his office was (200 Oxford Street) is now a Topshop, and they have an Eat area in the same space as where the canteen was located. If you ever decide to eat in the same place Orwell ate. Despite two years on the air, no audio records exist of Orwell’s voice.

During the War, Eileen started work at the Censorship Department at the Ministry of Information (now the Senate House–and the inspiration for the Ministries in Nineteen Eighty-Four) and then at the Ministry of Food.

14. He Finally Met Ernest Hemmingway

It always seemed that he and Hemmingway were in the same places at the same time, but never met. Hemmingway also fought a bit in the Spanish Civil War, and had lived in Paris the same time Orwell had (of course they didn’t run in the same circles). But Hemmingway must have been following Orwell’s career because, according to Paul Pott’s essay on George Orwell, Quixote On a Bicycle:

On another occasion when he got back to Paris, from a visit to the part of Germany reached by the now advancing allies, dressed in uniform (he was a War Correspondent for The Observer) and was staying at the Hotel Scribe, which was the Paris HQ for Allied War Correspondents, he looked in the register to see if there was anyone interesting to talk to. War Correspondents as such were, he said, terrible bores. To his delight he found Hemmingway’s name. He had never met him. He went up to his room and knocked. When told to come in, he opened the door, stood on the threshold and said, “I’m Eric Blair.” Hemmingway, who was standing on the other side of the bed, on which there were two suitcases, was packing, and what he saw was another War Correspondent and a British one at that, so he bellowed, “Well what the fucking hell do you want?” Orwell shyly replied, “I’m George Orwell.” Hemmingway pushed the suitcases to the end of the bed, bent down, and brought a bottle of Scotch from underneath it and still bellowing said, “Why the fucking hell didn’t you say so. Have a drink. Have a double. Straight or with water, there’s no soda.”

15. He Had Many Mistresses

Orwell was quite the womanizer, especially after he became a famous author. He had many woman friends that were lovers and then became friends. He had many friends with benefits. Once he had suggested a three-way with a lover from Southwold and his wife, Eileen, but was rejected. How did Eileen feel about all this? Did she know? She knew and didn’t seem to care, as they seemed to have an open marriage. If Eileen suffered, she did so silently.

16. He Had a Son—And Became A Single Father

Orwell had always wanted children, and always worked well with them (“I’ve always been good with animals” was one of his stranger quotes pertaining to raising children). The problem is, Orwell thought he was sterile. He never got an official diagnoses and just assumed he was sterile because, up to that point, he never fathered any children (he MAY have fathered a daughter in Burma, but this has never been proven). In the spring of 1944, Orwell and Eileen got word of a woman who couldn’t keep her baby and the two of them jumped at the chance to adopt. They got custody of a baby boy in June and named him Richard Horatio Blair (Richard, after Orwell’s good friend Richard Rees, and Horatio after his father’s brother). At first Eileen was unsure she could love another person’s baby, but she was quickly proven wrong as she took to the baby. George and Eileen became enthusiastic parents, and many of Eileen’s letters document Richard’s growing and developments.

Tragedy fell in late March of 1945, when Richard was only ten months old. Eileen was admitted for a hysterectomy to help with possible ovarian cancer. She had a heart attack due to the anesthesia and died on the operating table. Orwell was in Germany for some war reporting and Richard was with family. Orwell called her “a good old stick” but was devastated in private. He writes about going back to The Stores in Wallington several years after Eileen’s death, to grab any possessions he might have left so that the cottage could be rented to someone else, and some of the pain he felt could be shown in his writing. He maintained a rosebush at Eileen’s grave while he was still alive.

Friends expected Orwell to put Richard back up for adoption, but he refused. He began to care for Richard himself, with the help of a housekeeper named Susan Watson. Richard became devoted to George, wailing when George left their flat at 22b Canonbury Square, Islington, London. George called Richard his “mate” while woodworking, as Richard would pass him the nails (he allowed Richard to sleep with his leather hammer instead of a stuffed animal). George refused to spank Richard, as he saw the toddler as his equal. A series of photos exist by Vernon Richards showing George and Richard in November of 1946, and they show what a caring father George was.

17. He Finally Found The Fame He Was Looking For

When Animal Farm was published in August of 1945, it became an instant hit. Although he had been well known among socialists and Communists, now Orwell was known throughout all social circles. Orwell started to have more money come in than he had had in his entire life. He was delighted when a friend adapted his novel for the radio, and bought a radio for his flat for the occasion. One incident, as Susan Watson recalls: “Animal Farm was published while I was at Canonbury. On the publication day, George came home and said he had been slogging around the bookshops moving it from the children’s shelves to the adult ones.”

The publication caught the attention of his childhood friend, Jacintha Buddicom, when she found out that George Orwell was really Eric Blair. They re-developed a correspondence but never met, as Jacintha would become horrified by Nineteen Eighty-Four.

18. He Loved His Tea

His love of tea and his way of preparing it can be found in the essay A Nice Cup of Tea. He would often make ten or eleven heaping teaspoons of Indian tea in a gallon teapot. According to Paul Pott’s, this is what tea time with Orwell was like:

“Nothing could be more pleasant than the sight of his living-room in Canonbury Square early on a winter’s evening at high-tea-time. A huge fire, the table crowded with marvellous things, Gentlemen’s Relish and various jams, kippers, crumpets and toast. And always the Gentlemen’s Relish with its peculiar unique flat jar and the Latin inscription on the label. Next to it usually stood the Coopers Oxford marmalade pot. He thought in terms of vintage tea and had the same attitude to bubble and squeak as a Frenchman has to Camembert. I’ll swear he vaulued tea and roast beef above the OM and the Nobel Prize.”

According to Susan Watson:

“He was always back for high tea which was the main point of the day. He liked northern English cooking. Kippers were a prime favourite or black pudding boiled first, then fried with onions and served on a bed of creamy mashed potatoes. Then there would be Gentleman’s Relish on toast, or brown bread and butter or home-made scones with jam. We had cake twice a week. All this was accompanied by tea from a huge brown enamel pot. It was so strong that, when rationing allowed, it took eleven spoonfuls to brew (or rather stew it, since George liked it to stand for a while). This has driven me to prefer China tea. He also loved home-made jam.”

Watson would also serve Orwell his night-time hot chocolate in “his pink mug with a picture of the elderly Queen Victoria on it.”

His favorite brand of tea was Fortnum & Mason and Ty-Phoo Tips (according to the autobiography of George Woodcock, who would save Ty-phoo rations and send them to George from Canada), and his favorite brands of chocolate was Cadbury’s and then Fry’s, but only if Cadbury’s was completely gone from the stores.

19. He Loved His Junk

Orwell was a fan of junk shops, as can be found in his essay Just Junk–But Who Could Resist It?. At his flat on Canonbury Square, bookshelves would be crowded with his collection of mugs commemorating the Diamond Jubilee of Queen Victoria. In his room he had a sword from Burma. When his father died, he inherited various Blair family items, like a family Bible and a painted portrait of a Blair relative that he hung above his old-wicker Victorian era chair. Behind the chair was his scrap screen, a screen once meant for in front of the fireplace but was now used to put various photos he cut out of magazines and postcards; arranged in such a way as to tell a story. He was very proud of this screen and mentioned it in the essay. One room, in a few flats he lived in, was always dedicated to his carpentry/woodworking tools. He loved working with his hands, even though at times he wasn’t very good at it. One time George made a chair, and would have others sit in it, much to their discomfort. A lot of these items can be seen in the Vernon Richards photos.

20. He Moved To An Island Getaway

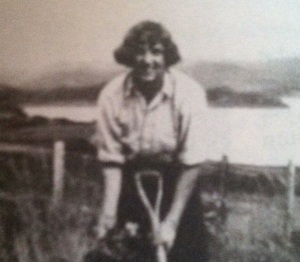

In the summer of 1946 George, Richard, and Susan moved to a house on the Island of Jura, off the coast of Scotland. It was a house he first visited in 1944 and he went ahead with it after Eileen’s death as a way to get away from the hectic demands of being a famous author in a populous city (not to mention the heavy smog of London probably was terrible for him). The house is called “Barnhill”, is located near the north of the island, and is owned by the Fletcher family. Soon after arriving, George’s younger sister Avril arrived (Marjorie and Ida had died around the same time as Eileen), causing friction between her and Susan. It is a fight that Susan eventually lost and she would end up leaving a year later, helped by the fact that Orwell thought her boyfriend was a Communist spy.

Orwell had meant for Barnhill to be just a summer location, with winters being spent back at Canonbury Square. This would have been healthier for him. But George being George decided to stay for the winter of 1947 and spent all of the year 1948 there. It was at Barnhill where Orwell typed out the final manuscript to Nineteen Eighty-Four, in the room above the kitchen.

Avril Blair digging for peat on Jura.

21. He Almost Got Sucked Into a Whirlpool

In 1947 George, Avril, Richard and Marjorie’s three children (Jane, Humphrey and Lucy) went camping at a semi-ruined “bothy” at Glengarrisdale on the west coast of Jura. Avril and Jane decided to walk back because the lifeboat everybody was in was too small. On the way back, the four of them encountered the dreaded Corryvreckan whirlpool and their dingy overturned. George managed to save Richard and the group climbed up onto a patch of land on the skerry of Eilean Mor. While the older kids were miserable, Orwell found it all very exciting and droned on about a bird he found while looking around. They were saved by a passerby, and George more or less shrugged off the incident when questioned by Avril and Jane.

22. Writing Nineteen Eighty-Four Was a Grueling Process For Orwell

The book isn’t that long, and is shorter than some of his older books. But it took forever to write. He first began writing it in 1946, but was bogged down by reviews and articles for newspapers. He had wanted to finish it in the summer of 1947, but didn’t get it done. Due to his advancing illness with tuberculosis, the book took longer and longer to write. The book had originally started being set in 1980, then 1982, and finally 1984 as the writing process dragged on. He spent most of 1948 typing out the final manuscript, sometimes being forced to type it out while in bed, when he couldn’t find a typist to come out to Jura.

The original title was The Last Man In Europe. But his publishers, Secker & Warburg, thought that Nineteen Eighty-Four was a better title.

Sonia Brownell, circa 1949

23. He Became A Husband For A Second Time

Soon after finishing the manuscript and sending it off to his publisher, Orwell was forced to leave Jura for good in order to be in the hospital. He left in January of 1949. He first went to a hospital at Cranham in Gloucestershire and then ended up in the University College hospital in London. He attracted even more fame after Nineteen Eighty-Four was published, in June of 1949. He began to use his fame to try and attract a second wife; someone to love and someone to help with his growing and increasingly complicated finances. He found the right woman in Sonia Brownell, a once-time lover that he had met because she worked at the newspaper Cyril Connolly was editor at. They married in his hospital room in October of 1949.

24. He Wrote A Communist Blacklist

Towards the end of his life, Orwell wrote out a list of notable writers and entertainers that, he felt, were not suitable to contribute to the Information Research Department’s anti-communist propaganda activities, i.e. those he felt were sympathetic to Communist causes. He had been keeping names in a notebook since the mid-1940s and wrote out his official list in 1949. They included such names as actors Charlie Chaplin and Michael Redgrave. Names that appeared in the notebook but not official list included actress Katherine Hepburn, poet Cecil Day-Lewis (father of actor Daniel Day-Lewis), George Bernard Shaw, John Steinbeck, and Orson Welles. One version of the list is still a British state secret.

25. He Died Alone

Early in the morning of January 21, 1950, an artery in Orwell’s lung burst, suffocating him and killing him instantly. He was forty-six years old. Avril and Richard, out on Jura, found out through the news the next morning and hasty plans were made to attend the funeral.

Orwell had voiced his wishes to be buried in according to Anglican rites and in the cemetery closest to wherever he was to die. The closest cemetery was full, so friends were able to pull strings to have him buried at All Saints’ Churchyard in Sutton Courtenay, Oxfordshire, England (tradition holds that atheists cannot be buried in a church graveyard, but friends were able to convince the owners that having George Orwell in their cemetery might bring it better publicity). His grave simply reads, “Here Lies Eric Arthur Blair. Born June 25, 1903. Died January 21, 1950”.

Sonia Orwell helped run Orwell’s estate until her death from cancer in 1980. Although a very intelligent woman, Sonia was not good with finances and she became bankrupt towards the end. In the 1950s, she allowed the Central Intelligence Agency of the United States to finance an animated movie based on Animal Farm. When she saw how they changed the ending, she refused to allow it to be shown in classrooms and felt, to the end of her life, that she had betrayed George.

Richard Blair was raised by his aunt Avril and her husband, Bill Dunn (whom she married soon after Orwell’s death) in Scotland. Throughout most of his life he kept a low profile, but since retirement has been more public about his father and the few memories he has of him. Richard has two sons of his own, and some grandchildren. His chosen career was in the agricultural field, and even worked for the British government as an agricultural agent.

References:

George Orwell: A Life by Bernard Crick

Orwell: A Wintery Conscience of a Generation by Jeffrey Myers

Orwell: The Authorized Biography by Michael Shelden

George Orwell by Gordon Bowker

Orwell Remembered edited by Audrey Coopard and Bernard Crick

Orwell’s London by John Thompson

Literary Lives: George Orwell by Peter Davidson

Remembering Orwell by Stephen Wadhams

Eric And Us: A Remembrance of George Orwell by Jacintha Buddicom

And many thanks to Peter Duby for helping me with mistakes!

On all of the other websites I looked at not one did what I required (at least 8 facts about George Orwell that are at least a little bit interesting! These were great facts that are perfect for my work

Thanks for the site.

Pingback: Some Updates « Writing As I Please

This is great! Thanks for the info 🙂

ps. I just love the word ‘slogging’

Pingback: حقائق ومعلومات شيّقة عن رواية جورج أورويل المثيرة للجدل.. 1984 | تيكي توك تكنلوجيا

Great site I am on it in class now